by Mike Crispen December 14, 2025

Have you ever wondered why the Torah (First five books of the Bible) can feel so scandalous at times? Stories like Tamar and Judah, or Lot and his daughters, seem almost out of place—especially when they interrupt the noble arc of Joseph’s descent and rise in Genesis. Yet this year, as the reading of that very portion coincides with Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights, the Torah seems to suggest that redemption is rarely born from polished stories. Hanukkah echoes the story of all Scripture: broken vessels are not discarded, but repaired through truth and return, so that light may dwell in them again and lead us back to our Creator.

Perhaps the Torah is teaching us that what we call “scandal” is often the raw material through which God exposes broken vessels and begins the slow work of preparing the world—and the individual—for redemption.

Tamar, Judah, and the Two Paths of Redemption

The story of Judah and Tamar appears in the Torah at a moment that feels almost disruptive. Joseph has just been sold into slavery, torn from his father and carried toward Egypt, and the narrative seems poised to follow him all the way down. Instead, the Torah slows its pace and turns its attention elsewhere. That pause is not a detour. It is an invitation to see that two redemptive paths are unfolding at the same time.

Joseph stands at the center of the first path. He is the beloved son, singled out by his father, sent to observe and report, entrusted with dreams that point toward a future he does not yet understand. Because he is favored, he is resented. Because he speaks what he has been given, he is rejected. His brothers strip him of his cloak, cast him into a pit, and sell him away. Yet the Torah never abandons a single refrain: God is with Joseph. His descent is not abandonment; it is preparation.

This is the pattern later described as Mashiach ben Yosef—the righteous one who suffers, is rejected by his own, and works salvation from within exile. Joseph does not confront his brothers or claim authority over them. He endures, he interprets, and he preserves life. Only later, when famine brings his brothers before him, do they finally recognize who he is. They bow, not because Joseph demanded it, but because truth has a way of asserting itself in time.

Running alongside this hidden redemption is another story that cannot remain hidden. While Joseph is carried downward to Egypt, Judah goes down of his own accord. His story is not about rejection, but failure of responsibility. He steps away from his brothers, fails Tamar, and allows injustice to stand uncorrected. Where Joseph’s suffering is imposed, Judah’s crisis is moral. And unlike Joseph’s story, Judah’s cannot be resolved quietly.

Tamar forces what Joseph’s brothers avoided: recognition. The same words—haker na, “recognize, please”—that once concealed Joseph’s fate now expose Judah’s failure through the sudden recognition of a “coat.” Faced with the evidence, Judah speaks the sentence that reshapes everything: “She is more righteous than I.” He does not defend himself or shift blame. He speaks plainly and publicly. In that moment, kingship is born—not through dominance or certainty, but through repentance.

From Tamar comes Peretz, whose name means “breach.” It is an unsettling name, but an honest one. Redemption, the Torah teaches, does not arrive through smooth succession. It breaks through places already fractured. From Peretz comes Boaz, a man marked by restraint, attentiveness, and care in how he uses his authority. Yet even this line is incomplete on its own.

That is where Ruth enters the story. She comes from Moab, descended from Lot, Abraham’s nephew—one of the broken branches of Abraham’s father Terach that drifted away and never fully rejoined the covenant. Ruth brings with her the humility of exile and the clarity of choice. She does not inherit belonging; she commits to it. Her loyalty becomes the thread that binds Judah’s repaired kingship to the wider, scattered family from which it once separated.

When Ruth and Boaz come together, the Torah is doing more than resolving a family narrative. Two wounded paths are being woven into one. Joseph’s world of exile and endurance meets Judah’s world of responsibility and leadership. The suffering servant and the repentant family are no longer separate trajectories. They become a single story pointing toward redemption. A family that once turned away from their brother, sincere in their devotion but divided in their hearts, was later reunited through recognition and redemption. What first appears scandalous becomes the means by which justice and mercy—Gevurah and Chesed—are ultimately revealed.

This pattern speaks powerfully to those entrusted with authority today, especially police officers. Officers are often asked to live the Joseph side of the story—to endure criticism, to absorb pressure, to do the work faithfully even when misunderstood or unappreciated. That endurance matters. Communities depend on officers who can remain steady under strain. But the Torah’s warning is subtle and important: endurance alone does not complete the work.

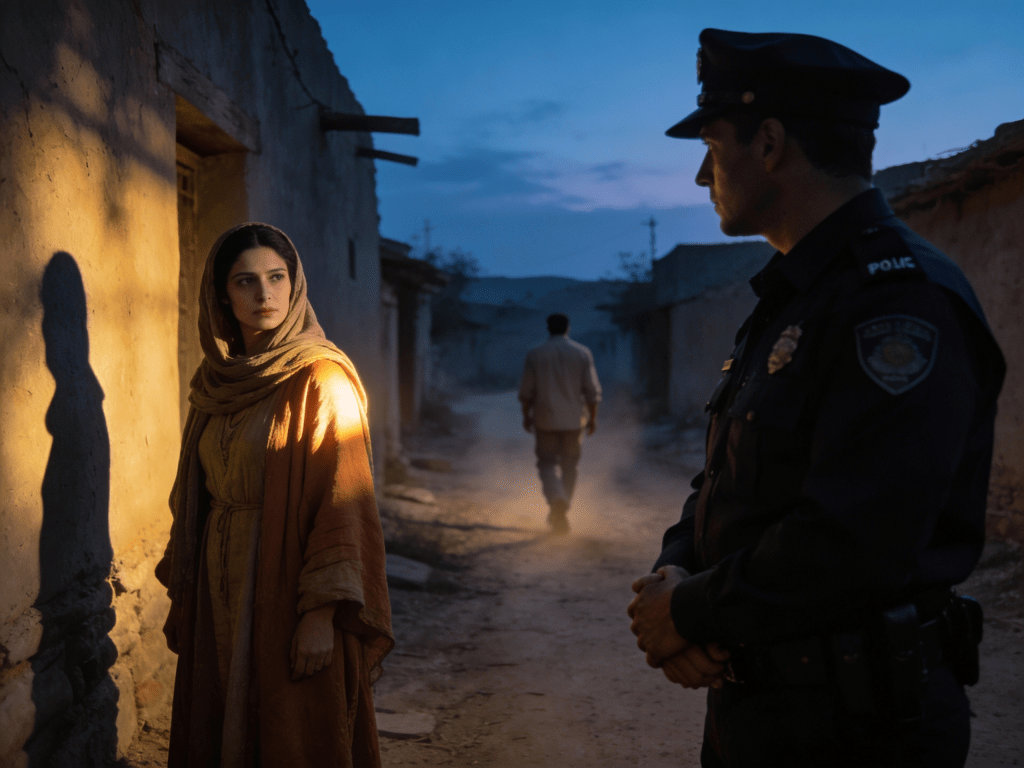

Judah’s story speaks just as directly to the officer on the street. Like Judah, officers make decisions that shape outcomes for others, often under pressure and with incomplete information. Most of those decisions are lawful and well-intentioned, yet the Torah’s lesson is that good intention does not end the moral obligation. There are moments—after a stop, an arrest, a word spoken too quickly, or a choice made to move on—when integrity requires honest self-examination. Teshuvah, the act of turning back and repairing what has gone wrong, may at the street level mean acknowledging a mistake, adjusting in real time, extending dignity, or choosing restraint over force.

It may also mean acknowledging when you could have done more that day, but allowed distraction, gossip, or inefficiency to pull you away from the work of protection. In other words, it is the quiet work of turning moments that could become scandal into teshuvah—choosing repair over excuse, and responsibility over silence. That kind of leadership rarely earns recognition, but it preserves the moral center of the work. The kind of leadership expected by the community and those in your home.

The Torah never separates leadership from home, and neither does real life. Joseph’s endurance and Judah’s repentance do not remain confined to the public story; they shape the kind of men they become when no one is watching. The same is true for officers. The habits formed on the street—patience, restraint, humility, or their opposites—do not stay at work. They follow officers home, into marriages, friendships, and the way children learn what strength looks like. The quiet choice to act with integrity, to admit fault, or to extend dignity under pressure does more than uphold justice in a single moment; it protects the person you are becoming and the relationships that matter most. In that sense, the work of redemption the Torah describes is not distant or abstract. It begins in ordinary decisions, carried from the street to the home, and lived out one faithful act at a time.

Leave a comment